The Ethereum vs. Solana Paradigm

On Ethereum, smart contracts are immutable by default. An upgrade requires complex proxy patterns. Solana took the opposite approach: programs are upgradeable by default. Every Solana program has an upgrade authority, a designated key that can modify the code, unless it is explicitly renounced.

This flexibility accelerates development but introduces a profound security trade-off. By 2026, upgrading smart contracts has shifted from a convenience to a critical infrastructure concern and, paradoxically, one of the most potent threat vectors on Solana.

Recent data and incidents underscore this tension. Solana's peak Total Value Locked (TVL) hit $14B in its rise, and virtually all that value resides in programs that can change overnight via an upgrade authority. Academic research like "The Dark Side of Upgrades" (2025) exposed thousands of issues in Ethereum upgrade mechanisms, and the lessons carry to Solana.

Let’s dive deep into security implications revealed by recent exploits and research, including uninitialized deployments, "ghost" state bugs, and upgrade key compromises. Furthermore, we outline mitigation strategies, ranging from hardware key management to AI-driven diff analysis, and the future of secure upgrades on Solana. If you are a founder or CTO building on Solana, understanding these nuances is now table stakes for protecting your protocol and users.

1. Solana Architectural Foundations for Upgradeability

Understanding Solana's upgrade patterns requires a granular look at how Solana programs are deployed and how they differ from Ethereum's proxy model. At the core is Solana's design decision to decouple code from state.

1.1 Code as an Account, State in Separate Accounts

On Ethereum, proxies achieve upgradability by using the EVM's DELEGATECALL to call library code in the proxy's storage context. This preserves msg.sender and state, creating an illusion of one immutable address with evolving logic. Solana does not need a proxy contract to separate logic and data because that separation is native.

A Solana program's code lives in a special Program account owned by the system's BPF loader, while its state lives in one or more data accounts (often Program Derived Addresses or PDAs) owned by the program that store persistent data. When users interact with a Solana program, they call the program's public key (the Program ID). The runtime loads the Executable Data (the compiled code) and executes it. The code reads and writes to the provided data accounts.

Crucially, because code and state are already distinct, upgrading a Solana program means swapping out the program's executable data while leaving state accounts untouched. It is analogous to an Ethereum proxy redirecting to new logic, except here the blockchain does the redirection by updating the program's code reference. From a user's perspective, the program's address remains the same and all their data accounts remain intact; only the logic governing them changes.

This is why Solana upgrades feel seamless. One transaction can replace the code, and subsequent instructions immediately start executing the new logic. There is no Ethereum-style msg.sender forwarding issue, as calls always carry the original signer, and no gas refund for self-destruct. The Solana runtime simply ensures that after an upgrade, calls go to the new binary.

Implication: Solana provides an illusion of immutability with mutability under the hood. Users interact with a permanent Program ID, unaware the code can be changed at will by an authorized party. This makes trust assumptions paramount. Users must trust that the upgrade key won't suddenly swap the code for a malicious version. It also means any new code must be carefully compatible with existing state data, since all prior state persists.

1.2 Storage Layout vs. Account Data: Avoiding "Collisions"

In Ethereum proxies, one of the greatest pitfalls is storage collision. If the proxy and new implementation have misaligned storage slots, an upgrade can overwrite critical state. The community mitigated this via unstructured storage (EIP-1967) to tuck proxy variables into high, random slots.

Solana's model sidesteps literal storage slot collisions because state is explicitly passed in accounts. Each account's data layout is defined by the program's struct definitions (e.g., via Anchor's #[account] struct). However, Solana faces an analogous risk: data layout inconsistency between program versions. If you deploy a new program version that expects account data in a different format than V1, you can introduce corrupt state or unintended behavior. This is essentially a logical "collision" between old data and new code. Two scenarios illustrate this:

- Struct field reordering or type change: Suppose V1 of a program's Config account stores an

admin_pubkeyat bytes 0-31. In V2, a developer mistakenly changes the order or type of fields such that the first 32 bytes are now interpreted as something else, like au64counter plus padding. The result is catastrophic; the existing accounts' bytes haven't moved, but V2's logic will misinterpret them. An admin pubkey might become an arbitrary number, potentially disabling access control or enabling exploits. This is directly analogous to an Ethereum storage collision, just at the level of serialized data in an account.- Rule #1: Solana devs must never change the order or remove fields in an account struct without migrating existing data. The community standard, and Anchor's approach, is to only append new fields to the end of structs to preserve offset alignment.

- Default value pitfalls ("ghost state"): Even when only appending, Solana upgrades can stumble over uninitialized new fields. By appending, you ensure old accounts can still deserialize, as the new field simply isn't present, effectively defaulting to zero. This avoids a crash, but it can mask dangerous assumptions. The new code might treat a zero value as meaning "false" or empty, when in fact that zero is just a placeholder because the data wasn't set. For example, if you add a boolean

is_pausedand don't initialize it, all existing accounts seeis_paused = falseby default, which might be acceptable. But if you add a newtax_recipient: Pubkeyand assume it's a valid address, all pre-upgrade accounts will havetax_recipientset to0x111...111(the all-zero pubkey). If the program tries to send fees to this address, it will effectively send them to the system program or simply fail. This leftover implicit state is often called "ghost state" or logic debt: old data that the new logic doesn't explicitly handle and which can haunt the system later.

Mitigation: Solana developers have adopted patterns akin to Ethereum's defensive programming around storage: use explicit versioning and initialization for new fields. One approach is a "lazy migration," where the program detects an unset new field and populates it on the fly or treats the account as needing initialization. This ensures eventually all accounts conform to V2 format. However, lazy migrations themselves can introduce logic complexity and edge-case exploits. Another approach is writing a one-time migration instruction that iterates through accounts to update them, though this can be expensive and prone to error. Regardless of method, storage layout management on Solana is as critical as on Ethereum. The key is to avoid "state collisions" between versions: never let new code misread old data.

2. Deep Dive: Upgradeability Patterns on Solana (Keys and Control)

By 2026, the Solana ecosystem has coalesced around a few primary patterns for managing who can upgrade contracts, each with distinct trade-offs in security, decentralization, and agility.

2.1 Single Authority (Single Key or Single Signer)

The simplest pattern is a single upgrade authority, often the founder or core developer's key. This might be a ledger hardware wallet, but historically it was often a hot wallet kept on a server or local machine for quick access. The benefit is agility: urgent fixes or feature upgrades can be deployed immediately, without coordination. This was crucial in fast-paced early-stage projects where a bugfix might need to be rolled out within minutes.

The downside is obvious: a single-point-of-failure and trust. That one key can unilaterally change the contract to anything, giving it "super power". If the holder turns malicious or is hacked, user funds can be stolen instantly by upgrading to a malicious binary. As Neodyme's researchers put it, "the unfortunate reality is that most Solana programs have a single hot wallet upgrade authority," which means users are effectively trusting a single person's OpSec and honesty. Relying on a single upgrade key is now considered poor practice for mature protocols.

2.2 Multisig-Controlled Authority

Moving up the decentralization spectrum, many teams transfer the upgrade authority to a multisignature wallet, such as a 2-of-3 or 3-of-5 multisig account. In this model, an upgrade transaction must be approved by M out of N designated signers. The advantage is a significantly reduced risk of rogue action or a single key compromise. If one key is hacked or lost, the attacker still cannot upgrade without colluding with or compromising additional keys.

Multisigs also allow operational resilience. From a security standpoint, a multisig turns the upgrade event into a small coordinated decision, likely including review. However, security is only as good as the signers' security. If signers are all in the same organization, the risk of an inside job remains. Also, collecting multiple signatures may take hours or days, which is problematic for emergency bug patches. Teams must balance the threshold: too low might not improve security, while too high might be impractical for quick upgrades.

2.3 DAO or Time-Locked Governance Control

The most decentralized pattern is handing the upgrade authority to a DAO governance contract, where token-holders vote on program upgrades. In this model, the upgrade authority is a program (the governance program's PDA) which will only execute an upgrade if a governance proposal passes. Some projects implemented this via a time-lock, where the authority waits a set period (e.g., 48 hours) to allow users to exit.

The pros are maximal transparency and community trust. Users know no behind-the-scenes upgrade can occur, and any code change requires an on-chain vote. This largely eliminates the rug-pull risk from insiders. It also encourages thorough review, giving community auditors time to inspect the new code.

Cons include speed and complexity. DAO-controlled upgrades are slow; a critical security patch might need to wait for a quorum, which could be devastating in a live attack. Additionally, many DAOs are small or plutocratic, effectively devolving to a multisig. There is also the scenario of governance attacks, where an attacker buys tokens to pass a malicious upgrade. Despite these caveats, by 2026 more projects are moving toward DAO-governed upgrades for long-term control.

2.4 Immutable (Renounced) Programs

The final pattern is to remove the upgrade authority entirely, making the program permanently immutable. Solana's CLI provides a set-upgrade-authority --final command to do this. Once executed, the program's Upgrade Authority field is cleared, and the Loader will reject any future upgrade attempts. Many consider this the gold standard of trustlessness.

However, immutability is a double-edged sword. If a critical vulnerability is discovered, there is no way to patch it in place. The only recourse is to deploy a new program and migrate funds or users, which may be messy or impossible. The 2022 Serum incident presented a twist: Serum's program was technically upgradeable, but the key was compromised and effectively unusable. They opted to deploy a new fork (OpenBook) with a new authority, analogous to redeploying because of lost control. Immutability also means no feature upgrades, which can be a competitive disadvantage.

Upgrade Authority Management - Trade-offs (2026)

3. 2025 Insights: Security Taxonomies and Analysis

As upgradeable contracts became the norm, researchers in 2025 began categorizing the failure modes and developing tools to catch upgrade-related issues. Many lessons were learned from Ethereum's proxy exploits, but Solana's ecosystem generated its own set of concerns.

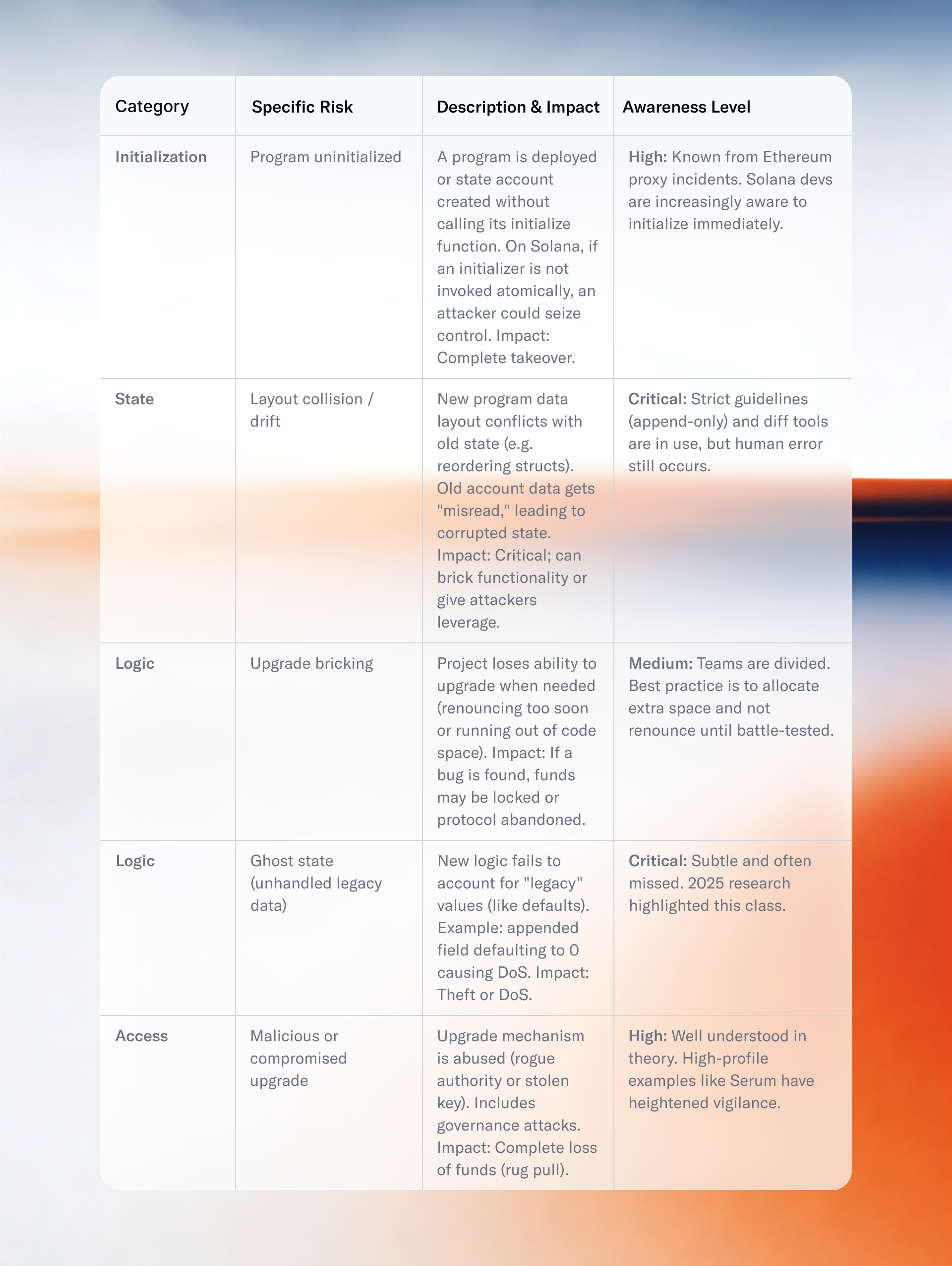

3.1 "The Dark Side of Upgrades": Risk Taxonomy

A comprehensive study in mid-2025 analyzed dozens of incidents and identified common upgrade-induced vulnerabilities. Table 2 adapts that taxonomy to Solana's context.

Taxonomy of Upgrade Risks (Solana Context)

3.2 Tools and Analysis in the Solana Ecosystem (2025)

To combat these risks, the Solana community has developed tooling and monitoring practices:

- Authority monitoring: Block explorers like SolanaFM and Solscan flag upgradeable programs and show the authority (e.g., known multisig vs. null key). Users can subscribe to alerts for upgrades.

- Static analysis and diff tools: Auditors use diffing tools to compare old and new program bytecode or Anchor IDLs. These tools catch changes in struct definitions or new instructions before the upgrade is executed.

- Security frameworks and versioning: Frameworks like Anchor encourage explicit version fields in accounts. A program can store a

state_versionand run migration routines when encountering old accounts.

4. Security Vectors and Failure Modes: Post-Mortem Analysis

Let's dissect two archetypal failure modes in Solana's upgrade story.

4.1 Upgrade Authority Compromise: The Serum Saga

One of Solana's most dramatic incidents was a crisis of upgrade authority custody. Serum, a flagship DEX, had an upgrade authority controlled by the FTX exchange team, not a DAO. When FTX collapsed in 2022, private keys were compromised, putting the Serum program update key at risk. This meant a hacker could deploy malicious code to redirect tokens.

The community response was swift: developers severed ties with the old program and deployed a fork called OpenBook with a community-held authority. Liquidity was migrated, leaving the old Serum program defunct.

Lessons: A protocol is only as strong as the security of its upgrade key. A single key represents a single point of failure. This incident drove many projects to move to multisigs or DAO control and highlighted the importance of transparency regarding who holds the keys.

4.2 "Ghost State" Exploit: Zero-Initialized Field DoS

This scenario involves a composite case based on real patterns observed in 2025.

- The Setup: A DeFi protocol upgraded to V2, appending a new field

tax_recipient: Pubkeyto its Config account. - The Issue: The developers did not migrate existing accounts, so

tax_recipientdefaulted to0x00...00(system program) in all markets. - The Bug: The new code immediately used

tax_recipientto transfer fee cuts during withdrawals. On Solana, sending tokens to the system program address fails. Thus, withdrawals began to error out. - The Attack: An attacker noticed the oversight and spammed small withdrawals to trigger the faulty fee logic repeatedly. This caused a partial Denial-of-Service (DoS) for honest users and clogged the fee backlog.

- Resolution: The team paused the program, manually set the

tax_recipientvia an admin instruction, and redeployed a patch.

Analysis: This is a prime example of "ghost state" or "logic debt". The default zero value was "weaponized" to disrupt logic. This parallels Ethereum exploits like Yearn yETH (2025) where untouched legacy variables led to fund drains.

Key Takeaways: Upgrades must consider initial state. Best practice is to immediately initialize or gate new features until state is migrated.

5. 2025 Case Study: Ghost State Bug Strikes (Step-by-Step)

To solidify the above, here is a condensed timeline of a real-world inspired ghost state issue.

- Upgrade deployed (V1 -> V2): Protocol X upgrades on Oct 15, 2025. V2 adds

tax_recipient, defaulting to0x00.... - Initial post-upgrade operations: Fees meant for

tax_recipientfail silently behind the scenes. - Attacker notices anomaly: Monitoring logs or diffing IDL, the attacker sees the unset field and confirms the bug with a test transaction.

- Denial-of-Service attack: Starting Oct 16, the attacker scripts a flurry of transactions to trigger fee distribution failures. Honest user withdrawals revert due to contention and errors.

- Detection and response: Team identifies the cause, pauses the protocol on Oct 17, and coordinates an emergency fix (manually setting the address and patching the code).

- Aftermath: Protocol X publishes a post-mortem. No funds were stolen, but trust was damaged.

6. Performance and Complexity: The Cost of Upgradeability

Beyond security, upgradeability has implications for performance and cost. Unlike Ethereum, where proxies impose gas overhead, Solana does not penalize upgradeable design in runtime execution. The costs come elsewhere:

- Upgrade deployment cost: Upgrading requires writing a new binary. Larger programs cost more in rent. Teams often allocate extra space (e.g., 2x headroom) upfront to avoid the "Program too large to upgrade" scenario.

Instruction complexity overhead: Upgrade safety checks (like lazy migration) consume compute units. While usually negligible, handling backward compatibility can bloat code. The bigger cost is complexity for auditors.

Security audit cost: Auditing upgradeable contracts costs 20-40% more than static ones. Auditors must review upgrade mechanisms, state migration, and version interplay. For example, if a token program audit is $X, an upgradeable version might be $X + 30%.

7. Mitigation Strategies and the Future of Upgradeability

Upgradeability in 2026 is a double-edged sword. Here are strategies to keep it safe:

7.1 Rigorous Upgrade Authority Management

- Use cold storage or secure multisigs: Avoid hot wallets. Use hardware-backed multisigs for upgrades. Segregate duties: routine ops keys should not be the upgrade key.

Decentralize control over time:** Plan a roadmap from solo key -> multisig -> DAO -> no key.

- Transparency: Publish multisig addresses. Explorers now use badges to indicate immutable or DAO-controlled programs.

Notifications: Wallet UIs alert users if a program has been upgraded since their last interaction.

7.2 Safer Upgrade Processes

Atomic upgrades with initialization: Bundle an initialization or migration instruction with the upgrade instruction. This ensures no window exists where the program runs with uninitialized state.

Guarding against incompatible state: Check version fields and revert if an old version is encountered. Some protocols require a `finalize_upgrade()` call to flip a version flag before resuming operations.

AI-assisted delta audits: Use AI tools to compare old vs. new logic and highlight risks like "Field added, default zero might be problematic".

Formal verification and fuzz testing: Use formal methods to prove that upgrades preserve invariants. Perform "shadow upgrades" on forked mainnet state to test for crashes.

Namespacing: Explicitly namespace account data for modules or reserve space for future fields to avoid collisions.

The future may see "functional immutability," where core logic is locked via on-chain checksums while UI features remain upgradeable.

8. Conclusion

The upgradeability landscape of 2026 is defined by a tension between operational flexibility and security integrity. Solana's mutable programs have fueled fast innovation, but also introduced a new class of risks.

For builders, the era of naive upgrades is over. Every upgrade is a potential vulnerability. "Legacy" state can compromise future logic if not handled with care. True robustness means minimizing changes or ensuring they don't harm invariants. We are likely to see upgradeability as a temporary phase for serious protocols: a means to achieve maturity, not an indefinite carte blanche.

Trust is hard to gain and easy to lose. Let's make sure upgrades remain a means of progress, not a "dark side" that overshadows innovation.

Get in Touch

Upgrading Solana contracts securely requires specialized expertise. At Cantina, we have identified ghost-state vulnerabilities and authority misconfigurations in protocols long before they hit production.

Whether you are managing upgrade keys, planning a major version upgrade, or need an audit, our experts are here to help. We offer:

- Upgrade architecture consulting: Choosing the right pattern (Multisig vs. DAO).

- State layout verification: Detecting layout drift or collision risks.

- Upgrade migration audits: Rigorous testing of V1->V2 transitions.

- Delta audits: Focused audits on changes between versions.

Ready to upgrade safely? Get your solana program audit quote.