Technical postmortem and maintenance lessons for long lived contracts.

On 8 Jan 2026, at block 24191019, we saw a transaction that led to the complete collapse in value of the Truebit protocol token. Truebit was one of the first protocols built specifically to scale Ethereum mainnet, launching back in April 2021. The protocol aimed to allow off-chain computation to be verified on-chain, which would lessen the load the Ethereum network would face and increase users’ ability to ensure their computations are run. This on-chain verification was done through the staking of its ERC20 token (TRU) and incentives for verification.

By blockchain standards, this is a long-running protocol with many years of user interaction. That longevity is often treated as a proxy for security. The reasoning is simple: if there were a bug, it would have been found by now. So what went wrong, or more accurately, what had been wrong this whole time?

The Facts

When reviewing the offending transaction stack trace, the attack path stood out for its simplicity. The attacker called getPurchasePrice, then buyTRU (function selector 0xa0296215) which gave the attacker a price of zero for all the TRU they were buying. They repeated this multiple times, minting to themselves more tokens than what was the total supply. The attacker then called sellTRU to swap the newly minted tokens for ETH. Overall, the attack cost less than $40 to execute and returned 8,535 ETH (approximately $26MM) to the attacker.

Let’s put the relevant addresses on the table at the time of the exploit:

.png)

(Another address in the transaction is the block proposer 0x4838...5f97, who was paid by the attacker to ensure block inclusion, but is not relevant to the exploit.)

When looking up these addresses in Sourcify, the only contract with verified Solidity source is the TRU Token Proxy, which was compiled using Solidity 0.5.3. This compiler version predates features Solidity developers rely on today, including arithmetic safety checks, try/catch, numerous bug fixes, and even the constructor keyword. Ethereum itself has also changed significantly since then. Fees did not have the burn and tip structure they do now, transient storage did not exist, PUSH0 was not an opcode, and more. In the verified contract, we can also see an older and now incorrect pattern that aimed to discern if an address was an EOA or a smart contract.

function isContract(address account) internal view returns (bool) {

uint256 size;

// XXX Currently there is no better way to check if there is a contract in an address

// than to check the size of the code at that address.

// See <https://ethereum.stackexchange.com/a/14016/36603>

// for more details about how this works.

// TODO Check this again before the Serenity release, because all addresses will be

// contracts then.

// solhint-disable-next-line no-inline-assembly

assembly { size := extcodesize(account) }

return size > 0;

}

EIP-7702 has broken the assumption that EOAs cannot have code and storage, and we have seen multiple attacks against legacy contracts that rely on that assumption.

Our first hypothesis was that the exploit might be taking advantage of this behavior. To confirm the actual path, we needed to analyze the unverified bytecode.

To do that, we ran the Purchase contract bytecode through Dedaub’s decompiler and traced the call flow.

function getPurchasePrice(uint256 amountInWei) public nonPayable {

require(msg.data.length - 4 >= 32);

v0 = 0x1446(amountInWei);

return v0;

}

The first call to getPurchasePrice sanitizes the input and then simply wraps a call to the 0x1446 function. Here we present the decompiler output, adjusting it to be more readable.

function 0x1446(uint256 A) private {

// The total supply of TRU

S = stor_97_0_19.totalSupply().gas(msg.gas);

v2 = _SafeMul(S, S); // S^2

// THETA is a scalar chosen by the protocol, set to 75 at time of exploit

v3 = _SafeMul(THETA, v2); // 75 * S^2

v4 = _SafeMul(S, S); // S^2

v5 = _SafeMul(100, v4); // 100 * S^2

v6 = _SafeSub(v3, v5); // 100 * S^2 - 75 * S^2 = 25 * S^2

// R here is the reserve balance, part of this contract's storage

v7 = _SafeMul(A, R); // A * R

v8 = _SafeMul(S, v7); // S * A * R

v9 = _SafeMul(200, v8); // 200 * S * A * R

v10 = _SafeMul(A, R); // A * R

v11 = _SafeMul(A, v10); // A^2 * R

v12 = _SafeMul(100, v11); // 100 * A^2 * R

v13 = _SafeDiv(v6, v12 + v9);

// ((100 * A^2 * R) + 200 * S * A * R) / (25 * S^2)

return v13;

}

Let's make that formula more readable. The price for a requested amount of TRU token is given as:

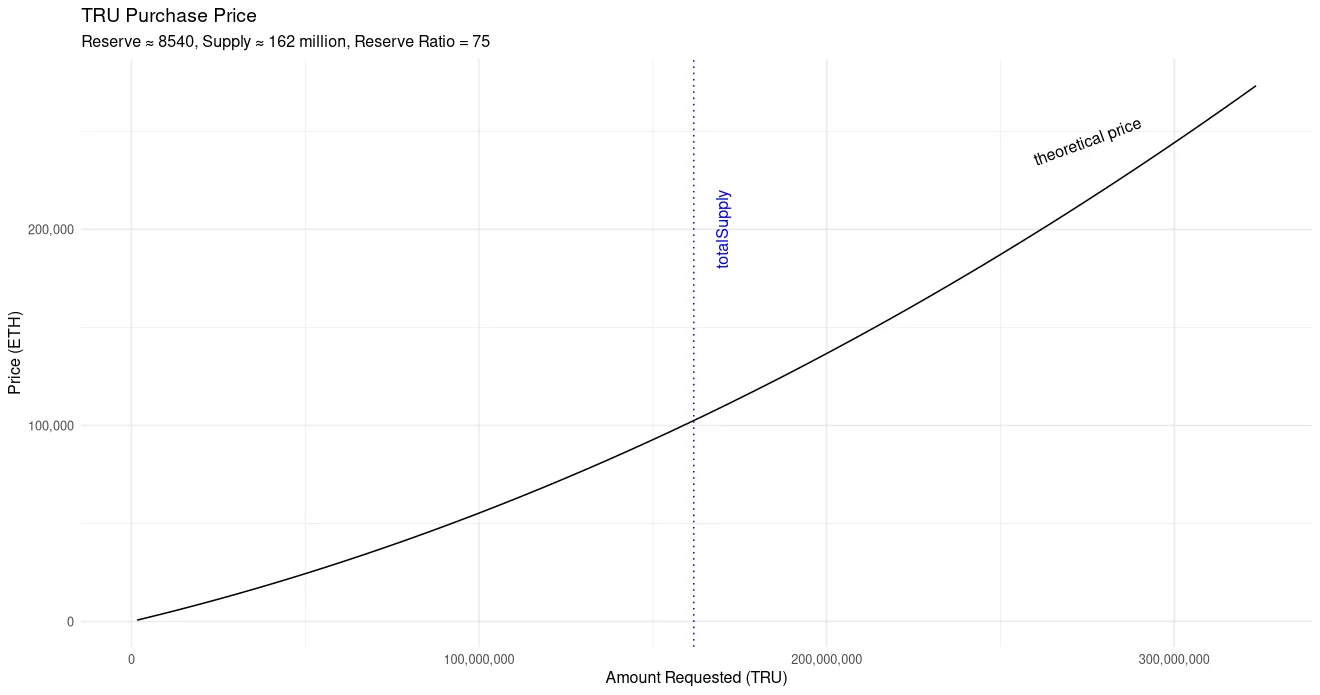

Charting this, we see the values the price function was supposed to yield when called.

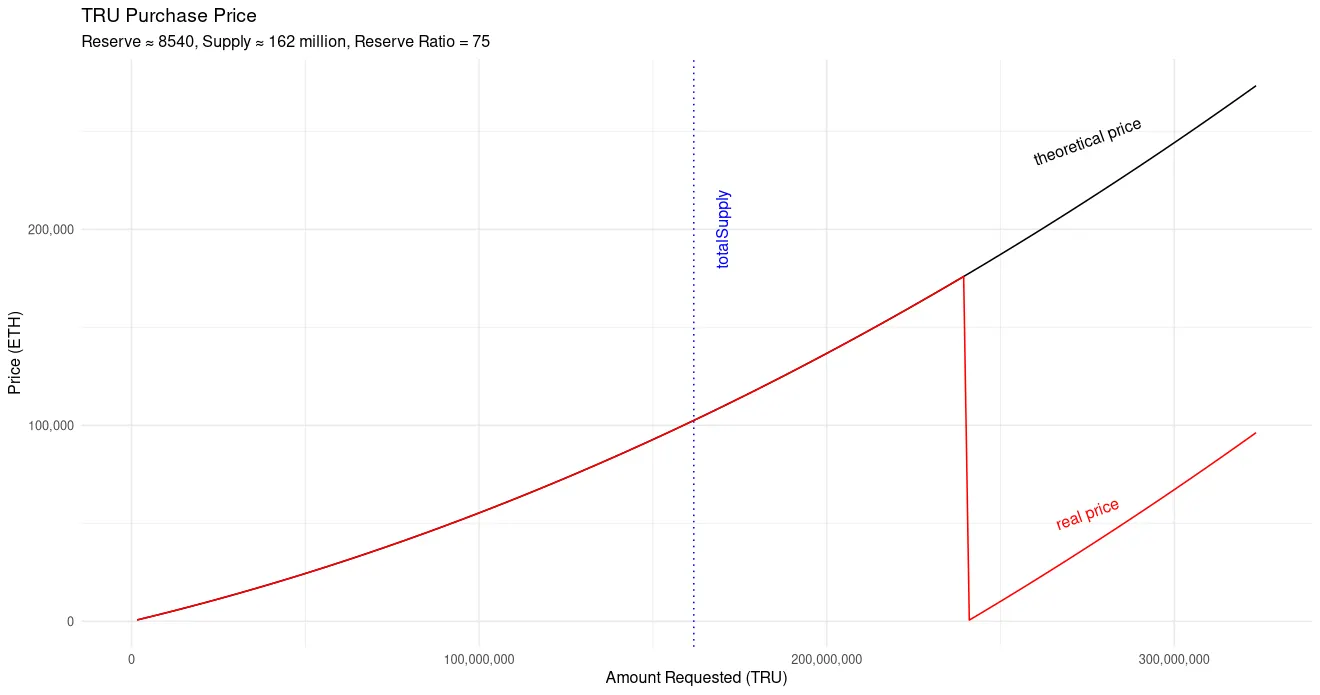

Did you notice the v13 calculation at the end? Throughout the function, arithmetic is routed through safe math helpers, but the final fraction includes a raw addition. In this Solidity version, that addition is not overflow-checked.

v13 = _SafeDiv(v6, v12 + v9);If those numbers are large enough, it will wrap around and become a much smaller number than it should be and if it is smaller than the denominator, the division operation will return zero. Indeed, that's exactly what occurred.

The attacker calculated the exact amount needed to drive the purchase price to zero. That zero price condition allowed them to mint unlimited TRU without providing capital.

What Went Wrong

When a failure is this severe, it is rarely the result of a single mistake. It is usually the outcome of multiple decisions and missed opportunities that compound over time. This bug appears to have existed since April 2021. At the implementation level, it began with a raw addition in the numerator of the final division in the pricing function. At a broader level, it reflects how a protocol’s security posture evolves, or fails to evolve, over years in production.

We could not find public audits or analyses of these contracts. It is also worth noting that the ecosystem in 2021 did not have the same baseline expectations, tooling, or shared security practices that many teams use today. Tools like symbolic execution (for example, Halmos) and fuzzing frameworks (for example, Foundry) are more widely understood now, but adoption is still uneven, and these tools are not always applied in ways that reliably catch edge cases.

Security posture matters because it determines whether issues like this are discovered early, and whether systems are updated as assumptions change. Truebit’s contracts were upgradeable. As compilers improved and Ethereum itself changed, upgrades, revalidation, and repeated independent review were opportunities to reduce risk. Each missed opportunity to revisit assumptions and strengthen the system increased the chance that a latent issue would eventually be exploited.

Lessons to Learn

Generative AI changes the economics of exploit discovery. In earlier eras, leaving code unverified may have added enough friction to slow down analysis. Today, large scale chain scanning and bytecode analysis are far more accessible. A dangerous pattern like isContract can be a starting point, and once a target is identified, decompilation and rapid iteration reduce the time between discovery and exploitation.

Protocols need ongoing security. In an ecosystem that keeps changing, being slightly behind current assumptions can be enough to create real risk. Teams should continuously evaluate how upcoming changes affect their threat model, and they should treat security as an operating practice, not a one time event. That includes audits and independent analysis, fuzzing and formal methods where appropriate, bug bounties and reward programs, documenting constraints and assumptions, and regularly reviewing integrations. There is always something worth rechecking.

Work with Cantina

Postmortems are only useful if they translate into action. If you want a second set of eyes on smart contracts, infrastructure, and operational risk, Cantina works alongside teams to build continuous assurance. That includes Web3 and Web2 audits, managed detection and response, and bug bounties designed for signal and speed.

Talk to our team, we’re available 24/7.

.png)